Let's follow the packet!

Everything on the Internet is sent in data packets. It’s time to get to know each other.

Note: I’m also learning. If you find any wrong or misleading information, please write to me.

Note: All the code you may find at my github in Blog repository

I’m sure you know whenever you download a new meme with cat, your browser is sending a packet with request and receive another packet or packets in response.

This packet usually looks like this:

+----------------------------------------------------+

| Ethernet frame |

| |

| +------------------------------------------+ |

| | IP frame | |

| | | |

| | +--------------------------------+ | |

| | | TCP/UDP frame | | |

| | | | | |

| | +--------------------------------+ | |

| +------------------------------------------+ |

+----------------------------------------------------+

You never notice them but they are the reason you can do whatever you want in the Internet. I will not talk about Ethernet frame, which mainly is used to find devices in the local network with MAC address (and also specify the IP version) and focus on the IP frame and TCP/UDP frame.

IP, TCP, UDP… What the heck does it mean?

I’m glad you asked! I will shortly describe it to you.

IP stands for Internet Protocol and was described in RFC 791 [1]. As we can read in the first paragraph:

The Internet Protocol is designed for use in interconnected systems of packet-switched computer communication networks. Such a system has been called a “catenet”. The internet protocol provides for transmitting blocks of data called datagrams from sources to destinations, where sources and destinations are hosts identified by fixed length addresses. The internet protocol also provides for fragmentation and reassembly of long datagrams, if necessary, for transmission through “small packet” networks.

So it is an universal transmission mechanism, which has its special place in the protocol hierachy[1]:

+------+ +-----+ +-----+ +-----+

|Telnet| | FTP | | TFTP| ... | ... |

+------+ +-----+ +-----+ +-----+

| | | |

+-----+ +-----+ +-----+

| TCP | | UDP | ... | ... |

+-----+ +-----+ +-----+

| | |

+--------------------------+----+

| Internet Protocol & ICMP |

+--------------------------+----+

|

+---------------------------+

| Local Network Protocol |

+---------------------------+

And how it looks from inside? Here’s IP header structure:

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

|Version| IHL |Type of Service| Total Length |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Identification |Flags| Fragment Offset |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Time to Live | Protocol | Header Checksum |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Source Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Destination Address |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Options | Padding |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

You can read what each of these fields means in [1]. For our program we need only byte-size of each field.

I will describe one very important field Protocol.

This field indicates the next level protocol used in the data portion of the internet datagram. The values for various protocols are specified in “Assigned Numbers”.

And to be more specific in RFC-790[2], where we can see following table (here just part of it):

Decimal Octal Protocol Numbers References

------- ----- ---------------- ----------

0 0 Reserved [JBP]

1 1 ICMP [53,JBP]

2 2 Unassigned [JBP]

3 3 Gateway-to-Gateway [48,49,VMS]

4 4 CMCC Gateway Monitoring Message [18,19,DFP]

5 5 ST [20,JWF]

6 6 TCP [34,JBP]

7 7 UCL [PK]

So if field Protocol in IP header has value 6 it means the next layer is TCP - Transmission Control Protocol (as in the first listing).

And it’s proparbly the most common case (with UDP - User Datagram Protocol). At this point you may think why is it the most common case? and here’s the answer (to be more specific in RFC-739[3])!

The Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) is intended for use as a highly reliable host-to-host protocol between hosts in packet-switched computer communication networks, and in interconnected systems of such networks.

That’s right, a highly reliable. And indeed TCP was design to provide that all packets will reach destination system.

Wait a moment! So it is possible to lose some packets?!

Unfortunately yes, but we will talk about this in another post.

We already know some basic stuff about TCP, so it is time to learn how it is built.

0 1 2 3

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 0 1

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Source Port | Destination Port |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Sequence Number |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Acknowledgment Number |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Data | |U|A|P|R|S|F| |

| Offset| Reserved |R|C|S|S|Y|I| Window |

| | |G|K|H|T|N|N| |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Checksum | Urgent Pointer |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| Options | Padding |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

| data |

+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+-+

And again if you want to know what every field means, please refer to [3] (which I highly recommend!).

After this very, very short introduction (but supported by many footnotes) we can start to code!

What we want to do in todays post is to catch those packets and decode each field, to get better understanding how it all works (it will be very basic parser, just to show you how you can do it yourselves. Some time ago I wrote very big parser and it will also be in my github as soon as I finish. Maybe you will be faster ;) ).

I assume you have basic knowledge how module struct work in python. Of course I will explain some, but if its the first time you ever heard about it, before you continue, please read [4].

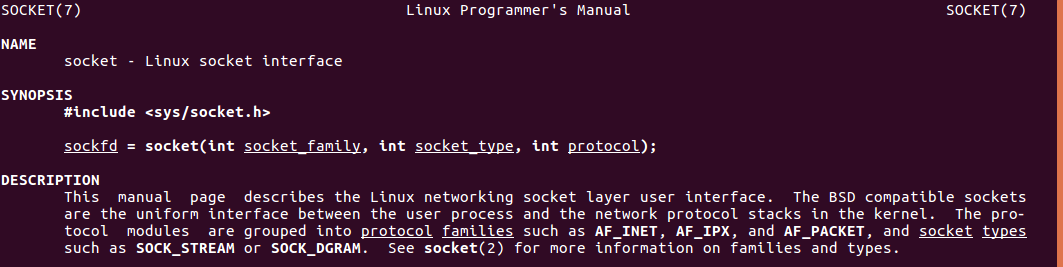

Let’s start with creating connection. To create one in Python you do not need much:

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_RAW, 6)

The AF_INET is Adress Family and IPv4, SOCK_RAW means Socket Kind Raw. Long story short, we will use IPv4 version and will get raw bytes from the socket.

And what ‘6’ means?

The 6 is from protocol. As I wrote earlier it refers to TCP. More information you will find in [5] and in manual of socket in unix libraries like socket(7). Just type in your console man 7 socket and you will see this:

Then you can go to socket(2) for more information and so on. Manuals are the greatest thing ever happend to programmers!

So when we have our socket we can parse the headers. As we listen only for INET packets we will parse IP header and TCP header. If you want to listen for whole packets instead of AF_INET use AF_PACKET, as you can read in man 2 socket:

AF_PACKET Low level packet interface packet(7)

Rembember that I’m using only IP packets because I want to show you how you can start with parsing packtes.

def ipPacket(data):

version = data[0] >> 4

ihl = (data[0] & 0xF) * 4

total_length, ttl, protocol, src_address, dst_address = struct.unpack('!2xH4xBB2x4s4s', data[:20])

return version, ihl, total_length, ttl, protocol, \

'.'.join(map(str,src_address)), '.'.join(map(str,dst_address)), data[ihl:]

def tcp(data):

src_port, dst_port, seq, ack, flags = struct.unpack('!HHLLH', data[:14])

data_offset = (flags >> 12) * 4

flag_urg = (flags & 0x20) >> 5

flag_ack = (flags & 0x10) >> 4

flag_psh = (flags & 0x8 ) >> 3

flag_rst = (flags & 0x4 ) >> 2

flag_syn = (flags & 0x2 ) >> 1

flag_fin = (flags & 0x1 )

return src_port, dst_port, seq, ack, flag_urg, flag_ack, flag_psh, flag_rst,\

flag_syn, flag_fin, data[data_offset:]

Let’s clarify some things. As version and IHL are in one byte and we want to separate them we can use byte shiffting. How does it work?

Assume I have this binary number a:

a = 01100010

If I perform a >> 4 in the result I get:

a = 00000110

As you can see it has shiffted all bits on right by 4 positions.

Ok, but why you are multiply ihl by 4?

You would knew that if you had read the RFC791!

Internet Header Length is the length of the internet header in 32 bit words, and thus points to the beginning of the data. Note that the minimum value for a correct header is 5.

Now it is clear, isn’t it?

Let’s go further and meet the struct module, one of Pythons best tools. It simply unpacking the data we are passing in bytes blocks described in the first argument. For exapmle:

src_port, dst_port, seq, ack, flags = struct.unpack('!HHLLH', data[:14])

This will unpack 14 bytes from data in this way:

- 2 bytes for

src_portas Integer, - 2 bytes for

dst_portas Integer, - 4 bytes for

seqas Integer, - 4 bytes for

ackas Integer, - and 2 bytes for

flagsas Integer.

More information you can find as always in Python docs [4].

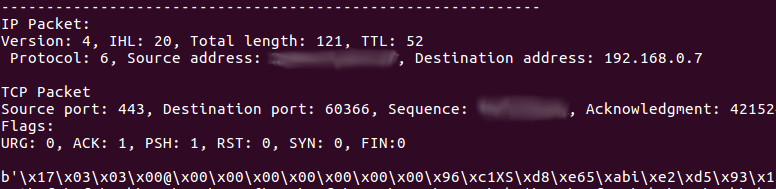

The last thing we will do in our sample program is create a main loop which will print it all out:

def mainLoop():

s = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_RAW, 6)

while True:

data, addr = s.recvfrom(1024)

version, ihl, total_length, ttl, protocol, src_address, dst_address, data = ipPacket(data)

print('------------------------------------------------------------')

print('IP Packet:')

print('Version: %s, IHL: %s, Total length: %s, TTL: %s\n Protocol: %s, Source address: %s, Destination address: %s\n' % (version, ihl,\

total_length, ttl, protocol, src_address, dst_address))

src_port, dst_port, seq, ack, flag_urg, flag_ack, flag_psh, flag_rst,\

flag_syn, flag_fin, data = tcp(data)

print('TCP Packet')

print('Source port: %s, Destination port: %s, Sequence: %s, \

Acknowledgment: %s\nFlags:\nURG: %s, ACK: %s, PSH: %s, RST: %s, SYN: %s, FIN:%s\n' % (src_port, dst_port, seq, ack, flag_urg, flag_ack, flag_psh, flag_rst, flag_syn, flag_fin))

print(data)

print('------------------------------------------------------------')

Now we have everything! Let’s test it!

And yes it worked! Now you know how to write simple parser for IP packets! You can discover a whole new world!

Why did he blur some data?

Ooo I’m glad you ask, but it is a story for another post!

And that’s it! Hope you enjoyed it!

[1]. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc791

[2]. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc790

[3]. https://tools.ietf.org/html/rfc793

[4]. https://docs.python.org/3/library/struct.html

[5]. https://docs.python.org/3/library/socket.html