Python Internals - part 1.

As Python recently became number 1 of most popular programming languages[1], it’s time to check whats under the hood!

Note: I’m also learning. If you find any wrong or misleading information, please write to me.

It was only matter of time when Python would be stand at the highest podium of programming language usage. The possibilities and easy of use make people all around the world falling in love with it. I’m sure you have heared the sentence that everything in Python is an object, but have you ever wonder how it all works? If not (and also if yes) I hope this series in which I will focus on Pythons interpreter internals will bring this a little bit closer to you : )

I will talk about CPython (2.7.8). If you want to get familiar with other Pythons implementation please refer to [2].

I really thought a lot, with what I can start this series (which I suppose will be loooong) and I thought we should start at the very beginning of Python implementation, which is:

C Structure Subtyping

As you know, Python is writen in the oldest of the greatest programming languages - C.

So how it is possible that one of the best objected oriented programming in the world is written in language which has so much in common with objectivity as tree has with an human eye?

It was possible due to very old trick of C language programmers.

But first things first.

If you open the sources of the language and go to /Include/ and open object.h you will see a beautiful description of something on which Python stands - definition of PyObject.

Let me paste a part of it here:

An object has a ‘reference count’ that is increased or decreased when a pointer to the object is copied or deleted; when the reference count reaches zero there are no references to the object left and it can be removed from the heap.

An object has a ‘type’ that determines what it represents and what kind of data it contains. An object’s type is fixed when it is created. Types themselves are represented as objects; an object contains a pointer to the corresponding type object. The type itself has a type pointer pointing to the object representing the type ‘type’, which contains a pointer to itself!).

Objects do not float around in memory; once allocated an object keeps the same size and address. Objects that must hold variable-size data can contain pointers to variable-size parts of the object. Not all objects of the same type have the same size; but the size cannot change after allocation. (These restrictions are made so a reference to an object can be simply a pointer – moving an object would require updating all the pointers, and changing an object’s size would require moving it if there was another object right next to it.)

Objects are always accessed through pointers of the type ‘PyObject *’. The type ‘PyObject’ is a structure that only contains the reference count and the type pointer. The actual memory allocated for an object contains other data that can only be accessed after casting the pointer to a pointer to a longer structure type. This longer type must start with the reference count and type fields; the macro PyObject_HEAD should be used for this (to accommodate for future changes). The implementation of a particular object type can cast the object pointer to the proper type and back.

So from this short introduction we know for sure 2 things:

- Everything in Python is accessed through pointers to the type

PyObject * - It has only two fields (which is not true for some cases, but we will discuss it in further posts regarding the objects):

typeandreference_count.

Let’s find it’s definition.

/* Nothing is actually declared to be a PyObject, but every pointer to

* a Python object can be cast to a PyObject*. This is inheritance built

* by hand. Similarly every pointer to a variable-size Python object can,

* in addition, be cast to PyVarObject*.

*/

typedef struct _object {

PyObject_HEAD

} PyObject;

As we can see it is very simple and contains only PyObject_HEAD macro (we will back to the text on top of it in a minute):

/* PyObject_HEAD defines the initial segment of every PyObject. */

#define PyObject_HEAD \

_PyObject_HEAD_EXTRA \

Py_ssize_t ob_refcnt; \

struct _typeobject *ob_type;

Now we have 100% sure, that documentation is true. We have ob_refcnt which is used by Pythons garbage collector and *ob_type which we use for casting to other Pythons objects.

Ok, ok, you tell me about all this things but what this have in common with this C Structure Subtyping?

Remember the text I told you not to worry about? C language is not objected oriented programming language but it has all of the tools, which can help us to simulate the objectivity!

I know, it may sound really scary at the moment, but just take a look how it works in Python:

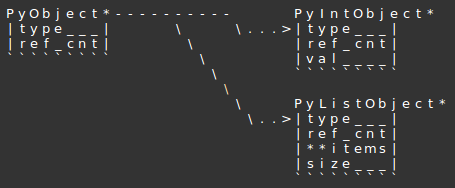

The fact that all of the objects starts with the same structure (PyObject_HEAD) give us opportunity to appeal to any of other Pythons objects using pointer of type PyObject*!

Data below this structure is not important untill we want to get there and to do it we just have to cast the type to our real type (PyIntObject* or PyListObject* in the example).

Oookeyyy…

It’s simpler than it sounds. Lets have a look at below code I wrote:

#include <stdio.h>

struct basic{

int a;

char b;

};

struct child{

int a;

char b;

short c;

};

struct child newChild;

struct basic* write(int a, char b, short c){

struct child *ptr;

ptr = &newChild;

ptr->a = a;

ptr->b = b;

ptr->c = c;

return (struct basic*) ptr;

}

int main(){

struct basic *ptr;

ptr = write(1, 2, 3);

printf("Sizeof ptr->a: %i\nSizeof ptr->b: %i\nSizeof ptr->c: %i\n", (int)sizeof(ptr->a), (int)sizeof(ptr->b),(int)sizeof(((struct child*)ptr)->c));

puts("-----------------------------");

printf("Address of ptr->a: %p\nAddress of ptr->b: %p\nAddress of ptr->c: %p\n", &(ptr->a), &(ptr->b), &(((struct child*)ptr)->c));

puts("-----------------------------");

printf("ptr->a: %i\nptr->b: %i\nptr->c: %i\n", ptr->a, (ptr->b),((struct child*)ptr)->c);

return 0;

}

It is similar to what Python does. Our function write return the pointer to our parent structure basic but in the body of function we declare object with structure child.

As you can see the first two variables int a; char b; are the same for both structures.

And this lets us to appeal to variable c of the child structure that we have assign in the write function, just by casting its pointer to struct child*!

Yea, sure, you can talk and talk, but does it work?

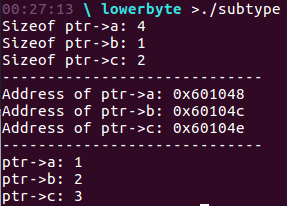

So let me show you then:

Sizes of variables of child struct matches, addresses of particular variables matches with their sizes and whats more the values matches!

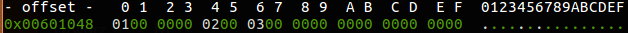

How does it look in memory? Like that:

Values are of course in little endian (the least meaning bytes at the begginig) and as you can see we have got the alignment! (if you do not know what is it, read my previous post).

With this little trick we implemented the very little part of objectivity in C language. But everything is ok as long as the beginnig variables in both structures are the same. What happend if they are not?

Lets modify our code:

#include <stdio.h>

struct basic{

int a;

int b;

};

struct child{

int a;

char b;

short c;

};

// Rest of the code remain the same.

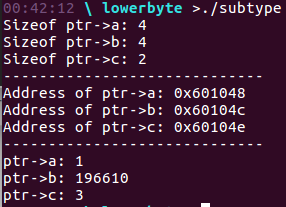

Execution:

Now our ptr->b variable is not correct.

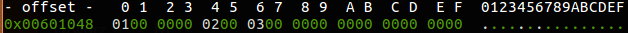

Quick look in the memory dump and now everything seems to be clear:

Ummm, did he paste the same picture twice…?

I afraid not, so what happend? The problem lies in basic structure variables size.

Now we have got 2 int, so 8 bytes, but we writing into memory using child structure so int, char, short. When we are reading from the memory using ptr->b we are using basic structure, because the function return pointer to it, so we are reading 4 bytes instead of one, like in child.

If we now get 4 bytes from the memory snapshot:

-offset-- | 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ....

0x00601048| 01 00 00 00 02 00 03 00 00 00....

ptr->a: 0x00000001

ptr->b: 0x00030002

ptr->c: 0x00000003

And guess what! Value 0x00030002 is our 196610 in decimal!

Ok, that’s it for today!

Hope you enjoy it!

[1] https://spectrum.ieee.org/computing/software/the-2017-top-programming-languages

[2] https://wiki.python.org/moin/PythonImplementations